James J Conway takes a tour of the writer’s main haunts during her time in the German capital…

Else Lasker-Schüler is celebrated as an artist, as a prose writer, and above all as one of the great German poets of the twentieth century. In 2019, I translated Lasker-Schüler’s episodic collection The Nights of Tino of Baghdad, which she wrote in Berlin and published in 1907, and which set me on the path to a more comprehensive collection of her pre-World War One prose (published by Rixdorf Editions in 2022). It also made me curious to know more about her time in the city. Where did she live? Who did she know? Did any of the stone witnesses to her existence survive the firestorms of modern German history?

Else (Elisabeth) Schüler was born to an assimilated Jewish family in Elberfeld (Wuppertal, in the Rhineland) in 1869 and died in Jerusalem in 1945, yet Berlin was home for the majority of her adult life, the stage for her creative personae and the crucible of most of her greatest works. She arrived in 1894 with her first husband, Berthold Lasker, but within a decade she had divorced him and married Herwarth Walden, by which time she was a fixture of bohemian Berlin.

Before World War One, Lasker-Schüler had established her uncompromising artistic vision, combining Jewish and Arab motifs to form an idiosyncratic Semitic realm of her mind. This construct was never confined to the page or the canvas; Lasker-Schüler appeared in public dressed as “Tino, Princess of Arabia” or “Jussuf, Prince of Thebes” and assigned roles in her imagined world to friends and associates.

Revisiting these figures and their physical settings evokes a whole German avant-garde milieu of the early twentieth century. It introduces us to writers, publishers, artists, gallerists, anarchists, utopians and café habitués searching for meaning beyond the reactionary confines of the Wilhelmine mainstream and even the more liberal Weimar Republic. Many of the buildings associated with Lasker-Schüler were destroyed during World War Two but these erasures themselves form a poignant memorial to a writer forced to absent the city at the peak of her renown.

Below, in approximately chronological order, are the key stations of Else Lasker-Schüler’s life in Berlin.

BRÜCKENALLEE

THEN: In 1894, Else Lasker-Schüler moved from Elberfeld with her husband Berthold Lasker and settled in Brückenallee in the central Berlin district of Hansaviertel. Lasker, a physician and chess master, hired a studio for his wife in the same street where she took art lessons. Nestled in a loop of the River Spree, the Hansaviertel was a prestigious neighbourhood at the time although it retained a creative edge, numbering both government ministers and artists among its residents, with two synagogues to serve its large Jewish community. Lasker-Schüler departed after the breakdown of her marriage in 1899.

NOW: This area was almost entirely destroyed during World War Two and the streetscape radically altered when it became a post-war showcase of high-rise modernism designed by the likes of Walter Gropius, Oscar Niemeyer and Alvar Aalto—West Berlin’s response to progressive urban development on the other side of the Wall. The building that stands where Lasker-Schüler once lived on Brückenallee, now Bartningallee, inhabits a somewhat less exalted class of post-war architecture.

CABARET PETER HILLE

THEN: Else Lasker-Schüler was present at the very dawn of Berlin’s fabled cabaret tradition, which flourished well before the Weimar era. In 1901 she joined Peter Hille, a prophet-like bohemian figure and the subject of Lasker-Schüler’s first prose work, for two evenings of cabaret presentations on Bellevuestraße, one night “erotic”, the other “tragic”; the former was—surprise—the more popular of the two. And Lasker-Schüler was there again in 1902 when Hille opened a cabaret under his own name at Dalbelli’s, a canalside Italian restaurant which was a popular bohemian meeting place.

NOW: Intensive wartime bombing left little standing around here other than the adjacent Matthäikirche (the tip of its spire is seen here). The site was cleared for an ensemble of cultural institutions, including the Neue Nationalgalerie which opened here in 1968. The design was a late work by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe originally earmarked for the Havana headquarters of Bacardí before post-revolutionary Cuba decided a modernist temple to an international consumer brand was off-message.

CAFÉ DES WESTENS

THEN: The one Berlin location indissolubly associated with Else Lasker-Schüler was the Café des Westens. This was the main bohemian hub of pre-World War One Berlin, with artists, writers and camp followers hatching plans which earned the venue the nickname of “Café Größenwahn”, or Café Megalomania. Lasker-Schüler was a frequent visitor with second husband Herwarth Walden, whom she married in 1903, and her infant son Paul. Actor Tilla Durieux remarked disdainfully that “the little family lived, I suspect, on nothing but coffee.”

NOW: The café fell out of favour with artists and writers around the start of World War One and closed in 1915; only the replica street lamp outside now suggests anything of the early twentieth-century streetscape. The space was later used as a cabaret, and in the 1920s “Dada Baroness” Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven could be found selling newspapers on this corner after her return from New York. The building was destroyed in the closing stages of World War Two, and the post-war Café Kranzler that arose in its place is now history as well, leaving only its sign and its festive Wirtschaftswunder canopy as an incongruous adornment to a branch of the weekend custody dad’s outfitter of choice, Superdry. Pro tip: don’t cycle around here. You will die.

LUDWIGKIRCHSTRASSE

THEN: Lasker-Schüler and husband Herwarth Walden lived on this street from 1903 to 1907, first in a building at this location and subsequently an apartment diagonally across the road. Parts of The Nights of Tino of Baghdad were written here. This area of Wilmersdorf was almost entirely new at the time.

Much of Lasker-Schüler’s activities in Berlin were encompassed within the bounds of what was then broadly termed the “New West”—a broad, orderly arrangement of bourgeois neighbourhoods presenting a stark contrast to the cramped and crooked corners which formed the capital’s historic heart. The couple’s neighbours included Lasker-Schüler’s publisher Axel Juncker as well as architect August Endell, who operated his practice and design school around the corner, where he wrote his major critical work The Beauty of the Metropolis (1908).

NOW: Clearly not the original building, which fell victim to wartime bombing, unlike its fortunate neighbours either side.

ARCHITEKTENHAUS

THEN: The Architektenhaus was a major venue for the avant-garde in Wilhelmine Berlin. In 1892 it hosted a scandalous exhibition by Edvard Munch, his first major showing outside Norway; in 1906 Lasker-Schüler first presented her Tino stories to the public here. The 1915 “Commemoration for Fallen Poets” hosted by Hugo Ball and associates at the Architektenhaus was a major event in what was later termed Dada.

NOW: The original building (and numerous neighbours) was erased in 1935 to make way for Hermann Göring’s colossal Air Ministry, which ironically survived intensive aerial bombardment in World War Two. In 1949 the German Democratic Republic was declared here; one edge of the building abutted the border later marked by the Berlin Wall. In the newly reunified city, a commission operated out of here to divvy up East Germany’s spoils. This is now Germany’s Finance Ministry.

AXEL JUNCKER VERLAG

THEN: Danish-born Axel Juncker was a bookdealer who kept a store specialising in Scandinavian literature near Potsdamer Platz. He also operated a publishing house at this more sedate location, issuing works by the likes of Rainer Maria Rilke, Kurt Tucholsky and Max Brod. Juncker published Lasker-Schüler’s first book of poetry (Styx, 1902), her first prose work (Das Peter Hille-Buch, 1906) and, in 1907 the third and last of their publications together: The Nights of Tino of Baghdad.

NOW: A war survivor on a quiet, tree-lined street.

KATHERINENSTRASSE

THEN: In 1909-11, Else Lasker-Schüler lived at this location with husband Herwarth Walden in a building that has since been destroyed. In 1910 Walden established a key twentieth-century avant-garde publication here, to which Lasker-Schüler provided not just articles but a name as well: Der Sturm (which Walden also applied to a gallery and an art school he ran). Its writers worked in an uncompromisingly intense style which Walden christened in a 1911 article for the journal: Expressionism. That same year Lasker-Schüler put a literary gloss on the couple’s split in a series of letters published in Der Sturm.

NOW: The site is now occupied by a long, low building of functional construction which houses a luxury car dealership.

JEWISH CEMETERY, WEISSENSEE

THEN: Else Lasker-Schüler’s beloved friend, Jewish bohemian anarchist Senna Hoy, was interned by Russian imperial forces before World War One; she scraped together the money to visit him in Moscow in 1913. He died there in 1914 and his body was brought to the Jewish Cemetery in Weissensee, in Berlin’s north-eastern reaches. In 1927 this cemetery would also be the resting place of the writer’s son Paul Lasker-Schüler and, less than a year later, her first husband Berthold Lasker.

NOW: The burial ground, subject of a 2011 feature-length documentary, is Europe’s largest surviving Jewish cemetery. In 2018 the UN recognised it as a site of outstanding biodiversity, and a long-running campaign is seeking to have it included on the UNESCO World Heritage register. Some parts are relatively intact, others left wild, with headstones toppled and smashed by falling trees. Unsure if I am stepping on what had once been paths, stung by nettles, I abandon my search for the graves of Paul and Senna Hoy. Anyway, it seems perverse to battle with this profusion of life just to momentarily reveal the markers of death. “Schlafe gut!” says one headstone – “sleep well!” I leave them to it. Pro tip: men, bring a hat.

HOTEL SACHSENHOF

THEN: The second plaque of this tour records Lasker-Schüler’s extensive residency of the Hotel Sachsenhof. However her association with this site was of even longer duration than the plaque suggests; she first occupied a room here in July 1918 when it was called the Hotel Koschel, meaning that she witnessed more or less the entire Weimar Republic from this busy street in Schöneberg. Oskar Kokoschka was another guest, and the hotel features in Emil and the Detectives.

NOW: The building not only survived the war impressively unscathed but continues to operate as a hotel, now painted in recent-divorcée-lipstick pink. Two doors down is the “Magnus Apotheke”, a pharmacy named for Lasker-Schüler’s friend Magnus Hirschfeld in the heart of Berlin’s main gaybourhood. Its window is full of protein powders.

DEUTSCHES THEATER

THEN: Although originally published in 1909, it took a decade (and the more sympathetic cultural environment of the Weimar Republic) for Lasker-Schüler’s major dramatic work, Die Wupper, to be staged. The venue for the 1919 production was the prestigious Deutsches Theater, founded in 1850 and famous as the object of an imperial hissy fit after Kaiser Wilhelm II, disgusted by the venue’s decision to mount a controversial Gerhart Hauptmann play in 1894, vowed never to return.

NOW: It took a while to get here as there was a marijuana protest marching down Unter den Linden. And they were so s l o w. Once I got to the deserted theatre and started snapping a friendly man cycling up to the front door asked if he should keep his bike out of frame, but I felt it added a humanising touch.

PAUL CASSIRER

THEN: In 1919, Lasker-Schüler’s works to that point were reissued by Paul Cassirer, who ran a publishing concern across the road from his primary business—an art dealership which was crucial in introducing modernism to Berlin. The new editions all featured artwork by the author herself. Cassirer was one of the targets of a bitter reckoning with her various publishers which Lasker-Schüler issued in 1925. The following year he committed suicide (the events are unrelated; Cassirer was engaged in a bitter divorce with Tilla Durieux—who we caught throwing shade at Else back in the Café des Westens—and shot himself in his lawyer’s office).

NOW: Viktoriastrasse, the street from which Paul Cassirer operated, was wiped from the map in World War Two. Where his publishing house once stood, traffic now makes its way to the tunnel under the Tiergarten, passing the Musical Instrument Museum which stood in as a music school in the mini-series Unorthodox.

JUSSUF ABBO’S STUDIO

THEN: Another target of Lasker-Schüler’s ire was Alfred Flechtheim, also an important art dealer and publisher. He operated a gallery on the Landwehr Canal, in a building that was also the venue for the first international Dada “trade fair”, in 1920 (in which Lasker-Schüler exhibited a collaboration with Otto Dix). In her essay she mentions a little footbridge that stood before Flechtheim’s gallery, expressing the wish that it might collapse from the force of her indignation.

The bridge led to a site on the opposite bank where Herwarth Walden once operated an offshoot of his Der Sturm gallery, where the Futurists exhibited in 1912. So Lasker-Schüler was more than likely familiar with the location when—around 1920—she met Palestinian-Jewish artist Jussuf Abbo, who had a studio in the building in which he had erected a Bedouin tent. At a particularly low point, Lasker-Schüler moved in with Abbo to care for her gravely ill son Paul, who died here in 1927.

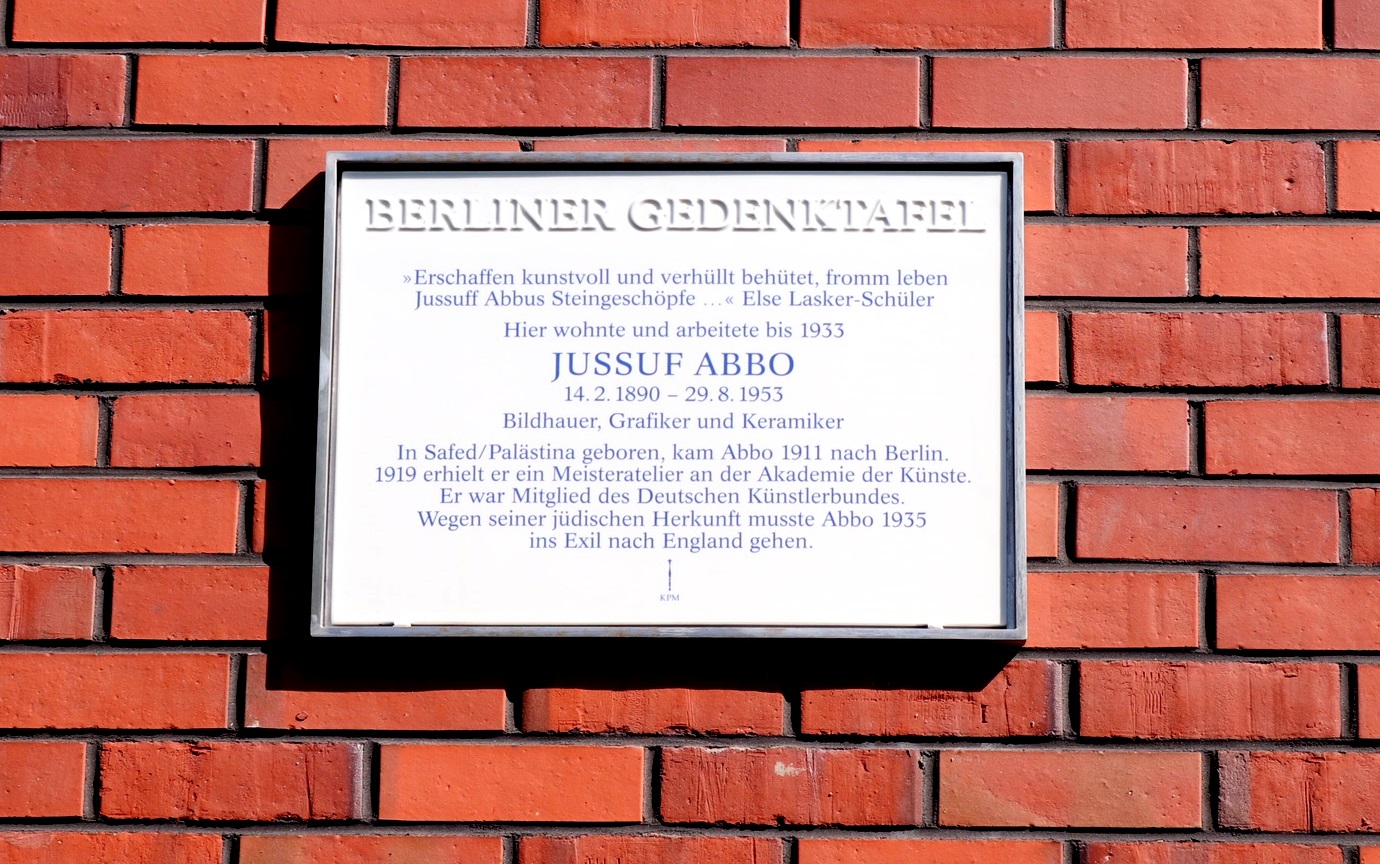

NOW: The site of Abbo’s studio is now occupied by a centre-left think tank. A plaque was recently unveiled on the building commemorating the artist with a quote from Lasker-Schüler (“Artfully formed and carefully shrouded, Jussuf Abbu’s stone creations lead pious lives”; “Abbu” was the original spelling of the artist’s surname). It was actually the war rather than Lasker-Schüler’s rage that took out the bridge, but a replacement now adorns this picturesque bend in the canal. Berlin’s recent development boom still hasn’t filled in this site, which serves as a depot for booze bicycles.

THEATER AM NOLLENDORFPLATZ

THEN: The Theater am Nollendorfplatz was a multi-disciplinary venue; here in 1908 Olga Desmond became the first dancer to perform nude in Berlin; in 1913 came the premiere of Hanns Heinz Ewers’s The Student of Prague, considered the first auteur film. Later under Erwin Piscator it was a key location for the Weimar performance tradition. Lasker-Schüler was a film fan, and a frequent patron of the venue which was just around the corner from her lodgings in the Hotel Sachsenhof.

In 1930 Lasker-Schüler attended the premiere of All Quiet on the Western Front here and was injured in a riot started by Nazis affronted by the film’s pacifist message. After receiving the prestigious Kleist-Preis in late 1932, she gave her last Berlin reading in the Theater am Nollendorfplatz, just two months before the Nazis seized power. At least one other public assault followed before Else Lasker-Schüler left Berlin in April 1933, never to return.

NOW: The theatre survived the war and has had various functions since, including concert venue and porn theatre. Here for Pride Week it was temporarily tricked out as another previous incarnation, the nightclub Metropol.

ELSE-LASKER-SCHÜLER-STRASSE

THEN: After living in extremely precarious conditions in Zurich, Else Lasker-Schüler was on a trip to Palestine in 1939 when the war broke out, and she was refused re-entry to Switzerland. She settled in Jerusalem where she died in 1945. In 1998 a section of Motzstraße, where she had lived throughout the Weimar Republic, was named for her.

NOW: The street is made up entirely of post-war buildings. Gentrification has made itself felt here in the new high-spec apartment block at one end of the street and the gay sex shop that closed down at the other. Sic transit glory hole.